Confessions of a ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ Boomer -- Part 2

/Are you like I was, on a spiritual search, looking for “more,” hoping to discover a greater sense of meaning and purpose in your life?

Are you struggling, like I was, to find something but not sure exactly what that something was or where you are going to find it?

Are you disillusioned, like I was, with the traditional approaches to religion you may have grown up with but not sure where to head instead?

If your answer to any of these questions is yes, then I hope the insights I’ve gained from my own spiritual journey will also help you discover and realize what you’re looking for.

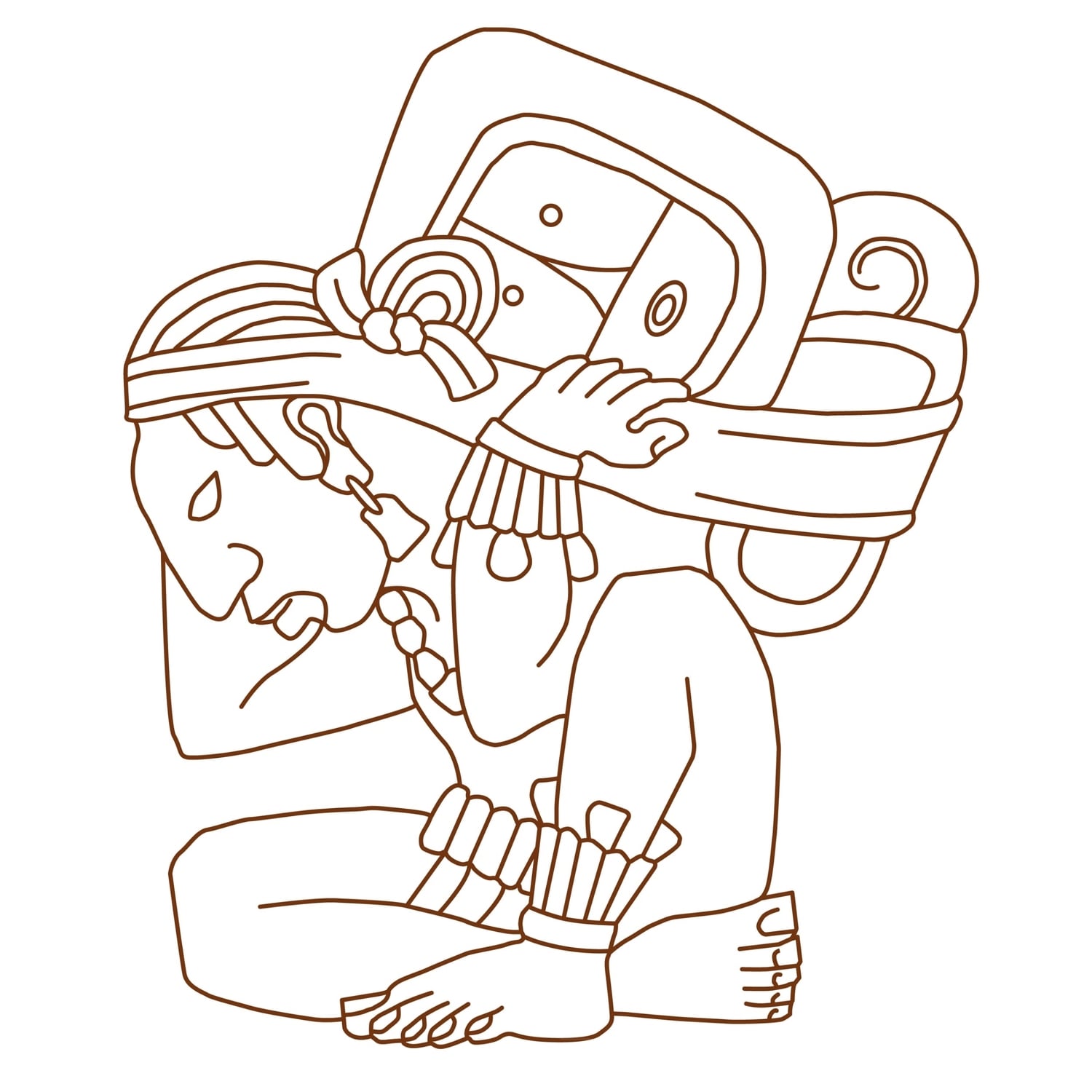

My studies with indigenous elders and participation in the ceremonial practices of the North American and Maya Indians led me to the “more” I had been seeking -- an authentic experience of the sacred and the transcendent nature of reality.

What took me completely by surprise, though, was that what I had hope to find was actually the direct experience of God I had on my vision quest (see Part 1).

Not only was a direct experience of God / Spirit / the Divine NOT what I was expecting, I never imagined this was even possible.

None of the indigenous elders I’ve studied with ever told me directly that the goal of my spiritual quest was to experience God / Spirit / the Divine. Yet I now know that was exactly where I had been headed and where I needed to end up.

During my journey, the clues were everywhere, “hidden in plain sight,” I just hadn’t recognized them.

Muskogee Creek Indian elder Bear Heart often spoke of the importance of ceremony and experiencing the presence of Spirit. Maya elder Hunbatz Men frequently remarked one of the great tragedies is that “so many believe that Hunab Ku [God / the Divine] is outside of us or out-there-somewhere-else,” and as a result feel so “disconnected from the giver of life, feeling lost and losing their connection to life itself.”

I now understood completely what Bear Heart and Hunbatz Men had been talking about. And I understood famed Lakota (Sioux) Holy Man Black Elk’s teaching that “We should understand well that all things are the works of the Great Spirit [who] is within all things.”

But rather than euphoric, my encounter with the Divine left me confused and bewildered. Although my experience was exactly what my indigenous teachers had described, it was completely at odds with most of the fundamental teachings about God from my childhood.

How could this be? Did I really have the experience I thought I had?

I now found myself on a new quest -- this one to try and find other spiritual traditions that explained what I experienced on vision quest.

I started by revisiting the Eastern spiritual traditions I had encountered over a decade earlier, studying them with my newfound perspective. Their wisdom teachings were filled with references to our ability to not only know, but also to experience union with, the Divine. I was relieved but still questioning.

Although I had found a bridge between indigenous and Eastern wisdom teachings, it was a Trappist Monk and an Ivy League professor who helped me discover a bridge back to my Judeo-Christian roots.

During this time, I had the good fortune of speaking privately with Father Thomas Keating during a ten-day Centering Prayer Retreat at St. Benedict’s Monastery at Snowmass, Colorado.

After listening to my experience, Fr. Thomas assured me that I had, in fact, “had a direct encounter with God. These experiences are not as unusual as one might think. Many people have had similar experiences, although they do not often openly discuss them.”

My conversation with Fr. Thomas was tremendously comforting but I was still plagued with this question: Why was this was never a part of my early Christian education?

Finally, the writings of noted scholar and McArthur Fellow Elaine Pagles provided the answers I was still seeking. Her books, The Gnostic Gospels and Beyond Belief, describe experiences of the Divine, similar to mine, that were widespread throughout the early Christian Gnostic communities.

Ancient Gnostic documents, Dead Sea Scrolls and Jewish mystical texts also reference specific techniques used to achieve a direct experience of the Divine (including fasting, prayer and singing sacred songs) that were identical to ones I was taught by indigenous elders (although the specific content and language was different).

I now knew that the ancient spiritual practices of the North American and Maya Indian shamans I studied with were no more obscure or esoteric than the wisdom teachings of the early Christian Gnostics and Jewish mystics. All shared a remarkably similar spiritual worldview, one that shared spiritual perspectives with Eastern spiritual traditions as well.

But why hadn’t I heard about any of this before?

The research by Pagles, scholar Bart Ehrman and others studying the history of the early Christian Church has shown that philosophical and doctrinal conflicts emerged during the early development of the church.

Once Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century, the church developed “Orthodox” positions to settle these conflicts. Emphasis was placed on “the separation between what is divine and what is human,” leading to the position that “God is wholly other.” (Pagles, Beyond Belief) Or, to return to Hunbatz Men’s observation, “[God / the Divine] is outside of us or out-there-somewhere-else.”

The church branded all teachings and writings that did not conform to the new Orthodox position as “heresies” and in 367 C.E. Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, ordered these writings (including those of the Gnostics) destroyed. Gnostic believers, as well as followers of other mystical sects, were branded as heretics, criminalized and punished.

And here’s the ultimate paradox: Church leaders today are dismayed that so many are looking for an authentic experience of the sacred and transcendent nature of reality outside the church. I believe that the reality so many are searching for is based on an actual experience of the Divine. But for almost two thousand years, the historical church has made that an impossibility because they have taken God out of the world and made Him / Her (more on this later) remote and inaccessible.

So here’s my confession (I hadn’t forgotten): I am, according to the perspective of my native religion, not only “spiritual but not religious” but also “pagan” (indigenous practices have always been considered pagan) and a heretic.

The “Good News” is that I found -- and you can also -- the spiritual experience we long for, but we may need to follow a different path than we’d planned.